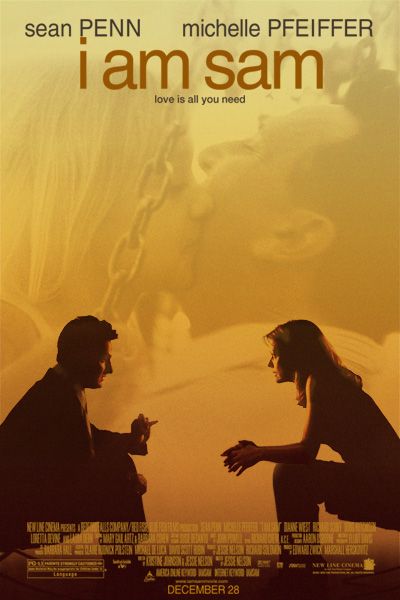

I am Sam: Review

A movie I enjoyed greatly in my childhood was the Edward Zwick produced drama “I am Sam”, which stars Sean Penn as the titular character—a man with the IQ of a 7 year old who is in danger of having his daughter taken away from him. The story is gut-wrenchingly tragic, painted in stale pastels and highlighted by whirling camerawork which brings us into the perplexed world of Sam. At the same time, however, there is an inexplicable sense of hope that radiates from every scene of this film, even before the cathartic ending which finally allows us to put down the tissue box one final time.

Most film critics will not agree with my evaluation of I am Sam. It has been over a decade since the theatrical release of the movie and despite critical acclaim for the leading performances of Sean Penn and Michelle Pfeiffer (Penn was nominated for an Academy Award for his role), the movie as a whole has been criticized for mawkish sentimentality. For this reason, I will endeavor to express my views of the film as a reflection of those who have questioned it.

The New York Times describes I am Sam as having a “sentimentality so relentless and [a] narrative so predictable that the life is very nearly squeezed out of it”. While I must congratulate the folks at the NY Times for some colorful wordplay, I must ask the question—is sentimentality, whether a surplus or surfeit, not a product of actors’ performances? In my humble opinion, stories about mentally retarded characters who almost inherently warrant sympathy are fundamentally prone to a hyperbolic scale of gooey cloyingness—the film can be as maudlin as a Nicholas Sparks novel or as grounded as a no-nonsense art film. The actors control how the words, oozing with potential sappiness, come to life. Penn and Pfeiffer, who portray the “Rain Man” and “Charlie Babbitt” of this movie, respectively, do not disappoint whatsoever. What’s more, I am Sam has the added virtue of a young Dakota Fanning, who gives a performance as Sam’s precocious daughter that could have single-handedly made millions for Kleenex. If someone was going to stand up and call Fanning’s performance “overly sentimental”, I might just throw myself into a wall because, dammit this is a child we are talking about!

Alas, we must move on to a criticism I am so hesitant to confront—that of Mr. Roger Ebert. I maintain the belief that Roger Ebert is, without question, the greatest film critic of all time. He may not be the unequivocal “best”, but his legacy and contribution is undeniable and the world of film lost a champion and a major talent with his passing earlier this year. However, Mr. Ebert makes a logically interesting argument that I must disagree with. To fully understand my argument against his, I would like to reproduce a paragraph of his review, in which he awarded I am Sam two out of four stars.

“The movie climaxes in a series of courtroom scenes, which follow the time-honored formulas for such scenes, with the intriguing difference that this time the evil prosecutor (Richard Schiff) seems to be making good sense. At one point he turns scornfully to the Pfeiffer character and says, “This is an anecdote for you at some luncheon, but I’m here every day. You’re out the door, but you know who I see come back? The child.” Well, he’s right, isn’t he? The would-be adoptive mother, played by Laura Dern, further complicates the issue by not being a cruel child-beater who wants the monthly state payments, but a loving, sensitive mother who would probably be great for Lucy. Sam more or less understands this, but does the adoptive mother? … Every device of the movie’s art is designed to convince us Lucy must stay with Sam, but common sense makes it impossible to go the distance with the premise. You can’t have heroes and villains when the wrong side is making the best sense.”

I would like to begin by stating that I agree with Mr. Ebert in all of his observations but none of his evaluations. Yes, the “evil prosecutor” played by Richard Schiff makes perfect sense when he scornfully condemns Pfeiffer’s lawyer character. Yet, the logic is irrelevant in this respect because he’s not attacking Sam—he’s attacking the seemingly PR-hungry, Porsche-driving lawyer who of course is morally questionable. Isn’t that the point? Pfeiffer’s character is established and developed on the grounds that she is, in the hearts of many and deep in her own heart of hearts, a cold person. What has Schiff’s character done but point that out? I am also a little taken aback by the typecasting of the “evil prosecutor”—the only reason that anyone would deem Mr. Turner (Schiff) as evil is because he is trying to give Lucy a different type of home and that in and of itself, is not evil. The issue with Laura Dern’s character, Randy, is equally puzzling. When has the moral ambiguity of situations ever been an issue with films? Wouldn’t the movie have been royally unentertaining if the foster mother was a cruel child-beater? The way that the film counteracts what one might think should happen only serves to disprove any accusations that I am Sam is “predictable”, as the NY Times states. The movie is anything but that.

I am Sam is a story that propagates the very values that Sam, inspired by the Beatles, wishes to indoctrinate—“All you need is love”. And the film does that in a fashion that is emotionally draining in the best way. The film ends with foster mother Randy giving up her rights to adopt Lucy and instead taking her place on Sam’s side of the stands—those who see the relationship that Sam and Lucy have know that it is the unadulterated kind of affection and care that so-called magic is based on. If you are like the movie critics of America, you will misjudge this movie based on the preconceptions of its message, which may seem utopian or divinely intervened. In reality, however, this is a movie of tremendous intricacy, well worth the watch and well worth your time.

8/10