Since the turn of the 21st century, the world has erupted into a state of technological frenzy. Even conquering the vast blackness of space and the coldness of our massive moon now seem so simple – stuff of the past. Today, traversing the globe is hardly a day’s journey, and sending a message the same distance might take only a fraction of second; an unfathomable notion to our mid 20th century selves. The world has shrunk to such an extent that if a man standing on the plains of the Russian east might stand on his toes and reach, he could touch the tops of the buildings of New York City. But still, as incredible as our new breed is, I doubt that many of us feel any more capable, or connected. In fact, our connectedness has left us isolated, and our capability less capable. Nothing is ever wholly good, and when we as a people embraced this age of lights and colour, we made sacrifices.

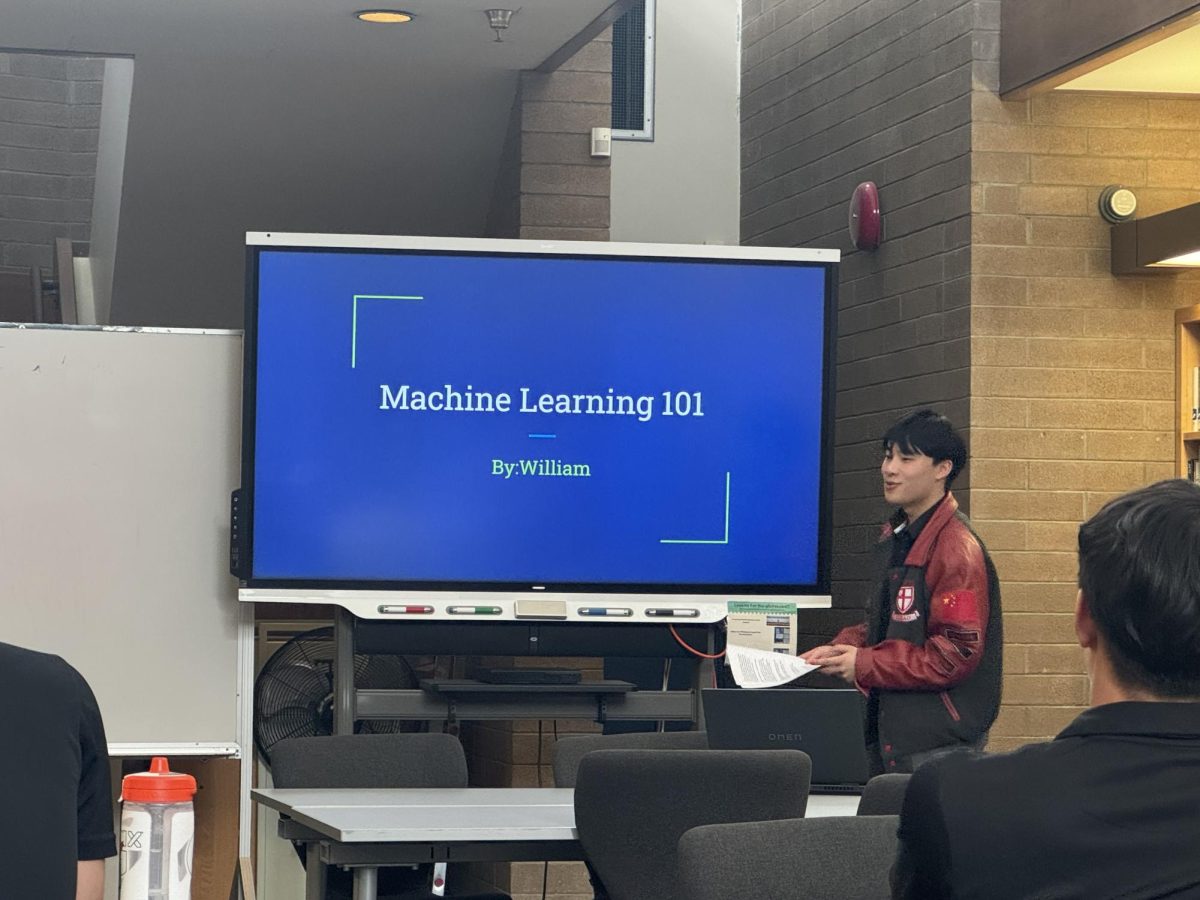

Even the most remote edges of the world have become a part of our integrated network. A Bedouin man might call his daughter in the city to ask how her day went while he grazes his camels on a seemingly detached stretch of desert prairie. I remember a conversation with a man that took my family and I camping through Egypt’s white dessert. He was standing high on his toes upon a dune, reaching with something in hand. We were truly alone, right spot in the center of nowhere. When I asked him what he was doing, he replied, “trying to send a text, service is a little spotty out here.” We might feel that isolation at this point is impossible, but in truth, the vast majority of us have been nestled comfortably into holes with our phones and computers – only to use those devices to speak with other dwellers in other holes. Our ability to see the undercurrents of misery in a face of joy or the flutter of terror in a confident voice has been untrained. Simplified is the terrific complexity of the human face to be read and interpreted with haste, in the form of emoticons. Interaction occurs on the basis of superficial text and image. Like a telegraph, we keep our letters timely and concise. No meaningful connection can be formed on a foundation of abbreviated phrases or 140 character tweets.

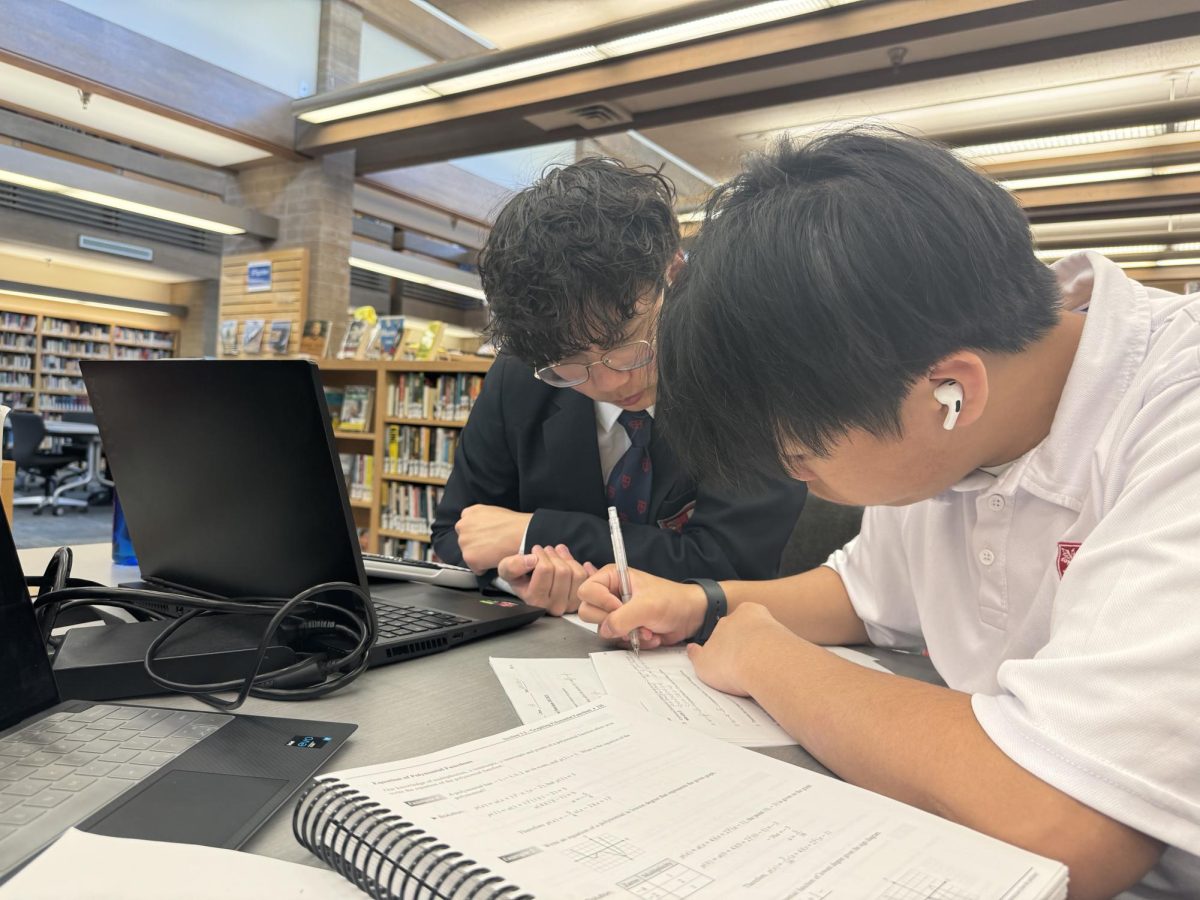

We are completely removed from the tactile world. Everything is flat. Machines are made simpler and simpler for the user, and we are made dumber and dumber. There was a time when every young North American boy was expected to learn the innards of a truck, to get his hands wet with oil and his shirt dark with mud. Those days are long gone. So long as there is fuel to burn and electricity pulsing through our towns, we can thrive. What a sad and limiting thing that is, to be so incompetent beyond the world of our machines that in the event of a global blackout, the human race might actually perish.

And the lights, the lights that manage to creep into even the darkest and most private corners of space. The average Canadian spends upwards of four hours each day gazing into the hypnotic glow of a computer monitor or television set. In fact, the sleep rhythms that have lived in our brains since this species was carpeted in thick fur and hunched like Quasimodo are beginning to cough, sputter, and die. In a survey given to 30 17-year-old high school students, 26 reported they slept better when they read, rather than used their laptop before bed. We are somewhat aware of the damage that can be done, but we manage to find a reason each night to wander the web. Those family dinners we spend sitting about the television like it has some worldly story to share have tricked our brains. The artificial light we take in past dusk deceives the pineal gland in the brain, making the body believe that day is still alive. As a result, 22 per cent of hormones like melatonin that are so crucial to our sleep are kept from release. Insomnia has become a thing of pandemic proportions. We are a newly nocturnal family, lying restless and full of thought in a night meant for sleep, and tumbling through our days in a painful and inhibiting lethargy. How freeing it would feel to again rise as the sun creeps over the horizon, and sleep when the darkness returns.

I would bet that the last true fresh start happened long, long ago. Technology has been so wonderfully persistent in tracking and recording each move we make. A computer can log the millions of key-strokes a user makes over a lifetime. Social media websites record with permanence every wrong action and mistake of every person blessed with an account. What a fearful thing it is that mistakes made as a nine-year-old can follow a person through infinite time, and with remarkable ease, poison each facet of his life. Scraps of everyone’s misdoings roam the web in search of an opportunity to do harm. Once released into the currents of this connected world, nothing can be retrieved.

Our lives have been made more concise, more direct and unfeeling. We lay awake in bed, and asleep during the day. Our devices do the talking for us. Relationships are built, or rather not built, on the basis of superficial interaction, and we are made dumber by our own genius. What a sad thing to witness. What a cold and callous darkness there is, lying among the lights and colour.