A relative of mine used to spend the summers of his youth working on a cattle ranch in Alberta. His stories were of hard labor, hard sun, cowboys and impossibly powerful horses. Often he would work in irrigation, passing the weeks toiling with pipes and screws, or digging trenches. He fell in love with the work, the feeling of it, the honesty of it, and the simple contentment he could derive from it. It made his heart sing. Working the earth and watching the animals cleared his mind of clutter collected from days spent about the busyness of his usual, urban home-life in Vancouver. In the 70s, passing time in such a way was not only normal, but also expected of youth.

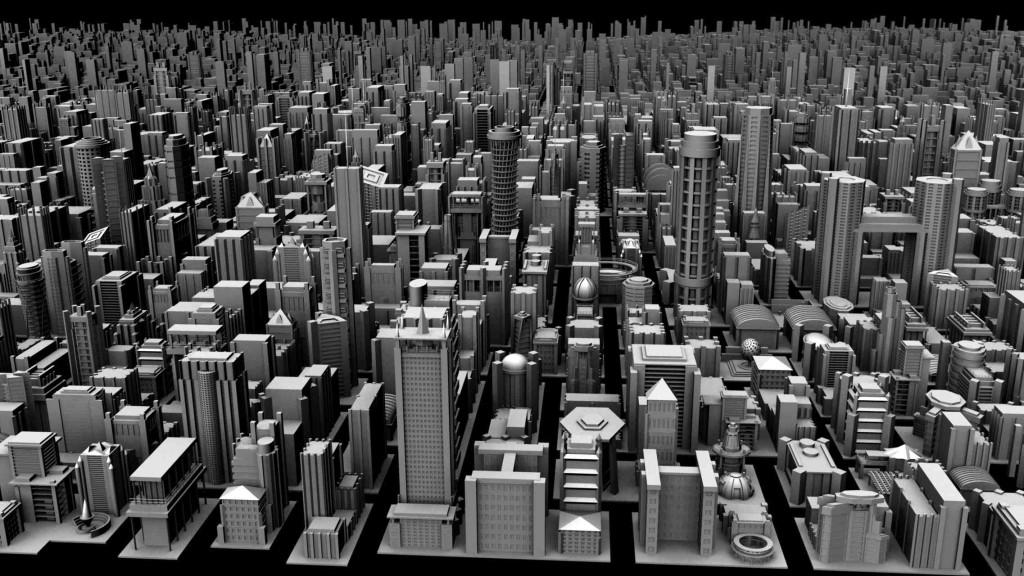

But times have changed; our summers bear little resemblance to the summers of our forbears. The reality of the 21st century is that the majority of us live in colossal urban centers. We carry smart phones and laptops, and have televisions. More kids end up working in shopping malls than on farms. Life for the child of 2013 seems to take place chiefly behind the sterility of a glass screen. Our days are spent so cleanly, so apart from the earth. We walk on perfect pathways. The nature we see on a day-by-day basis is only tamed nature, planted in faultless congruency. I would imagine it’s possible to travel between any two places in this city without stepping on a patch of dirt. Few of us can recall the last time we felt wholly caked in grime.

We are becoming a generation of spectators, living vicariously though the figures we see on television or in magazines. Media is fed in a constant, numbing flow. We trap ourselves in the mesmerizing gaze of flashing screens the way deer become trapped in the compelling glow of headlights. We are chained to our electronics. Our fear of having some fragment of the virtual world pass beyond our notice prevents us from experiencing life to its fullest extent, in the real world.

I came to this understanding last year, during an outdoor education expedition in Sayward, Vancouver Island with my school. We canoed as a company of ten, crossing though six or seven lakes over the course of five days, portaging the land that separated each lake. Of course, we were required to leave all electronics at home. With their ancient wisdom great mountains towered over the waters we paddled and in their sinews living rivers coursed towards the valleys below. Drifting through such untainted waters was truly freeing. We were thoroughly at peace, away from the rectangularity of our automated city lives. We were more energetic than our urban selves, more social, more curious, and healthier. We were far more comfortable sleeping on rough earth than in our padded mattresses at home; we even slept better. The exhaustion of our travels left us rested. The air felt cleaner in our lungs, and moving felt better than staying still.

It’s not as if we should expect everyone to ceremoniously burn their laptops and live like monks or bush-people. Technology and media are very much functional and necessary tools; they provide crucial services. Despite their addictive quality, they are most surely a blessing. All I’m saying is that as a hastily modernizing people, it is vital that we recognize the importance of breaching the precision of our urban reality from time to time to satisfy our embedded, human thirst for natural experiences. I think we would all feel just a little more clear-headed if we did.